I initially wrote and presented this paper about my composition Music for Social Distancing for the 2020 Aspen Composers Conference.1 If you’re interested in the work that is the subject of this paper, you can get the score and performance information on my site. The presentation included this performance of the work by Wichita State University’s Happening Now new music ensemble, with a little help from my friends.

Introduction

In March 2020, I and countless other musicians across the United States were asked to stay in our homes and limit our personal interactions as much as possible to limit the spread of the novel coronavirus. This impacted nearly every music presenter, performer, venue, and school in many ways. As many interpersonal interactions—meetings, lessons, and even parties—migrated to videoconference platforms like Zoom and Skype, it quickly became obvious that performing traditional repertoire would not be feasible over these platforms for a variety of reasons I will discuss momentarily. Even beyond the common practice period, more recent, flexible compositions pose similar challenges to remote performance. In this presentation, I will discuss some of the issues associated with remote ensemble performance, the compositional techniques I used in my work Music for Social Distancing to account for those issues, and the experiences with various readings and performances of the work in the months since I first published it.

The term “social distancing” was quickly and widely adopted by health and policy experts in the earliest days of the pandemic. The World Health Organization (WHO) and US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended that individuals maintain a minimum of six feet of space between themselves and others outside their household. However, it quickly became apparent that “social distancing” might not be the most apt description of this recommendation, and some adopted the phrase “physical distancing” instead. In a WHO press conference, Dr. Maria Van Kerkhove elaborated:

… [K]eeping the physical distance from people so that we can prevent the virus from transferring to one another, that’s absolutely essential. But it doesn’t mean that socially we have to disconnect from our loved ones, from our family. Technology right now has advanced so greatly that we can keep connected in many ways without actually physically being in the same room or physically in the same space with people. … So find ways to do that, find ways through the internet and through different social media to remain connected because your mental health going through this is just as important as your physical health.2

This idea, maintaining social bonds in spite of physical isolation, became very important to me as I was working on this piece, teaching lessons and classes remotely, and imagining what music could look like under these restrictions. I will continue to use the expression “social distancing” here, as it is more familiar, but I intend it to mean physical and geographic separation rather than social isolation.

Virtual ensembles

When institutions started canceling concerts and universities and conservatories started sending students home, I and many of my colleagues scrambled to find the best ways to move our performances, rehearsals, and classes to the Internet. A popular question in online music forums was “What application do I need to use to have my rehearsal online?”. The obvious assumption there is that there was such a thing. It turns out there wasn’t, isn’t, and likely won’t be any time soon, due to technical limitations.

One well-explored solution is that of so-called “virtual ensembles”, exemplified and popularized by Eric Whitacre’s Lux Aurumque virtual choir video in 2010. Virtual ensembles create a fixed recording and require a reasonably high level of planning, editing, and technical expertise. As recordings, they are fixed and do not unfold in realtime as live performances. Additionally, unlike most classical music recordings, they are not created in a way that allows performers to listen and react to one another, because they are not in the same room and at the same time. As admirable and impressive as virtual ensemble recordings are, I did not find them to be a very good substitute for the things that I missed most from the performances that I loved.

Chamber music

One particular thread in an online music teaching forum got stuck firmly in my mind. It was devoted to a question about how to do remote chamber music coaching, rehearsing, and performance. There were a number of suggestions that all centered around making multitrack virtual-ensemble-style recordings. Each time some version of this was suggested, the asker promptly replied “that is not chamber music!” I want to examine what chamber music is, and why I felt that remote chamber music performance required the creation of a new kind of repertoire.

In the simplest, most literal sense, chamber music is defined by the small size of the performing ensemble. It is the implications of that small size that make chamber music worth distinguishing from larger works. Conductorless musicians have greater responsibility for shaping the performance individually, listening, and reacting to one another, encouraging what James McCalla in the preface to his Twentieth-Century Chamber Music describes as “individuality as an essential part of [their] collectiveness”.3 This individual-collective dichotomy is what I find most appealing about chamber music. It is what allows chamber music to be subtle, and intimate, and exciting. However, these same features are also the first to falter when attempting remote performance over the Internet.

Reacting to sounds of other musicians in chamber music relies on the ability to hear nearly instantly every other musician in the ensemble. In a chamber ensemble setting where performers are positioned within a few feet of one another, the delay from the speed of sound traveling through the air is negligible, just a few milliseconds. Take those same players and move them to different locations connected over the popular Zoom videoconferencing platform, and the time it takes a player’s sound to reach their colleagues ears is likely in the hundreds of milliseconds, roughly equivalent to being spaced hundreds of feet apart. Even using specially engineered, low-latency solutions, it is difficult to achieve a level of precision most musicians would be comfortable with. The physical limitations of converting an audio signal to digital information, translating that over several network layers, and converting it back to audio, will likely always be too slow for live performance between musicians performing together from their respective homes. It’s possible that performances could be arranged by a synchronized click track, but that precludes flexibility and spontaneity in many of the same ways as virtual ensembles.

While latency is the largest and most prominent limitation for remote musical performance, it is not the only one. Services like Zoom, Skype, Google Meet, and others were designed to allow verbal conversations, which have a very different sound profile and performance characteristics to music performance. In addition to being more tolerant of latency, spoken communication does not have the same dynamic range or frequency range, and unlike music, conversations rarely have more than one or two simultaneous contributors. Because of these differences, videoconference platforms often compress the dynamic range and attenuate high and low frequencies of a music performance. They may also identify very soft sounds as noise, and attempt to remove them. When more than two players are sounding at the same time, the platform may decide to silence other audio feeds. Different platforms offer varying levels of control over the categories and degrees of audio processing, but none are built with the goals of music-making.

Working within extreme limitations often requires works to have a degree of flexibility. However, many popular examples of flexibly scored music—Terry Riley’s In C and Julius Eastman’s Stay On It—are open ended in certain parameters like texture, form, duration, and orchestration, but still require an extremely high degree of rhythmic precision (relative to a common pulse) and also ask each player to be acutely aware of every other player’s sound in real time.

Compositional techniques

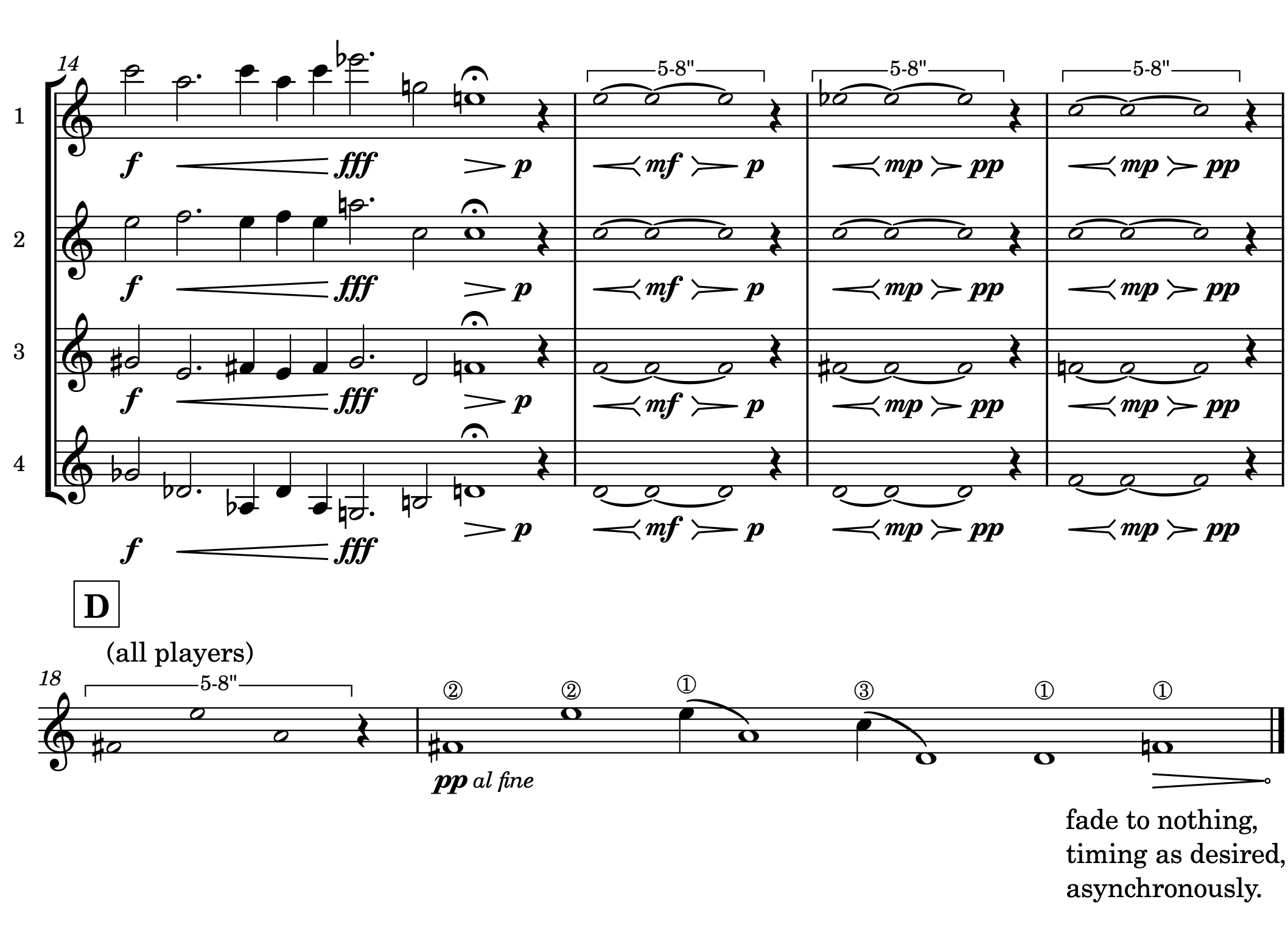

I wrote Music for Social Distancing for unspecified remote ensemble, four or more players and optional conductor, in March, with the intention of making it available to school ensembles who were starting remote instruction and other ensembles struggling to find something to do with what remained of their season. The work calls for performers to play from home over a videoconference, and the composite of all the players is streamed live to an audience. In this medium, I chose to focus primarily on the issue of audio delay, which I see as the most obvious barrier to remote performance. I also wanted to make sure that players were truly making chamber music by listening and reacting, not just contributing their discrete layer at roughly the same time as the rest of the ensemble.

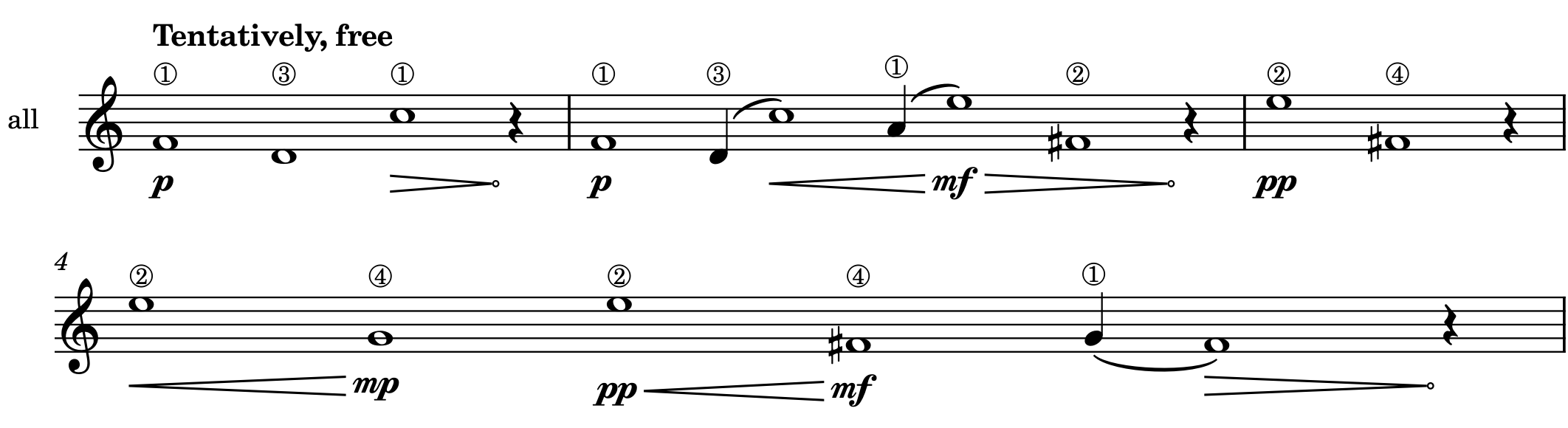

The opening and closing sections of the work move forward through latency and listening. All four parts play the same lines (with octave adjustments as needed). Each note or two- to three-note gesture is labeled as being initiated by one of the four parts, and the other players only move to that gesture after they hear someone else play it. For example, the piece opens with an F which is initiated by Player 1. The other three players wait to play the F until they hear it from Player 1. All players sustain this until Player 3 moves down a third to D, at which point the other three join the new unison. The result is a kind of floating cloud of canon-like imitations that drift based on who the leader is, how clearly they are heard by the other players, and what the player-to-player latency is at that moment.

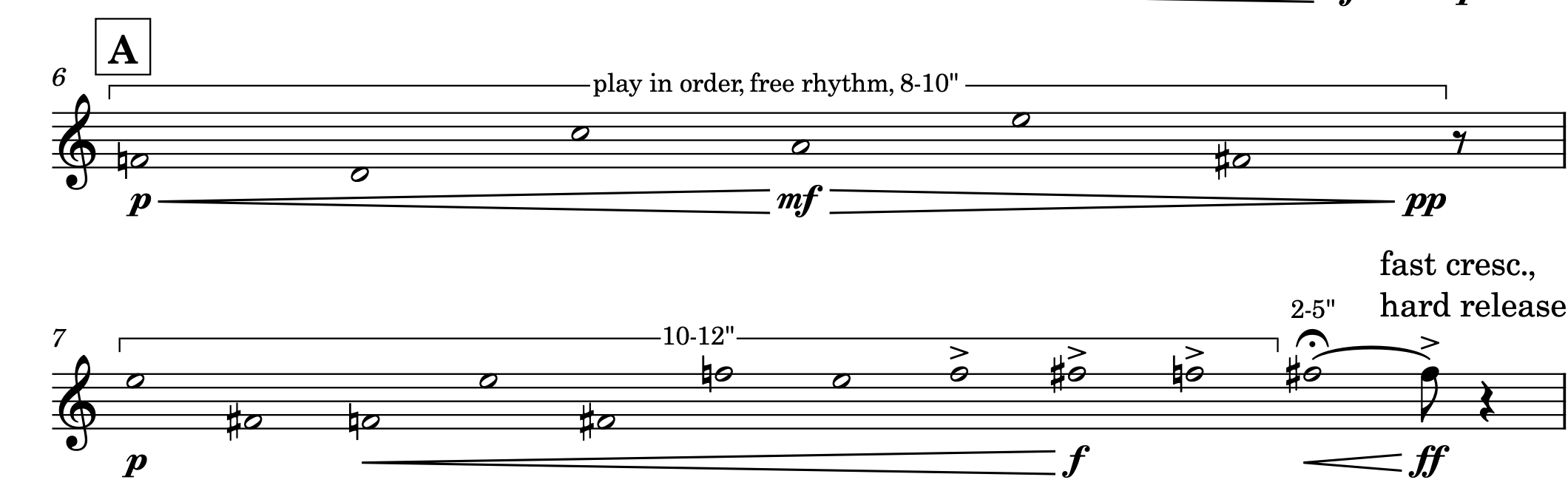

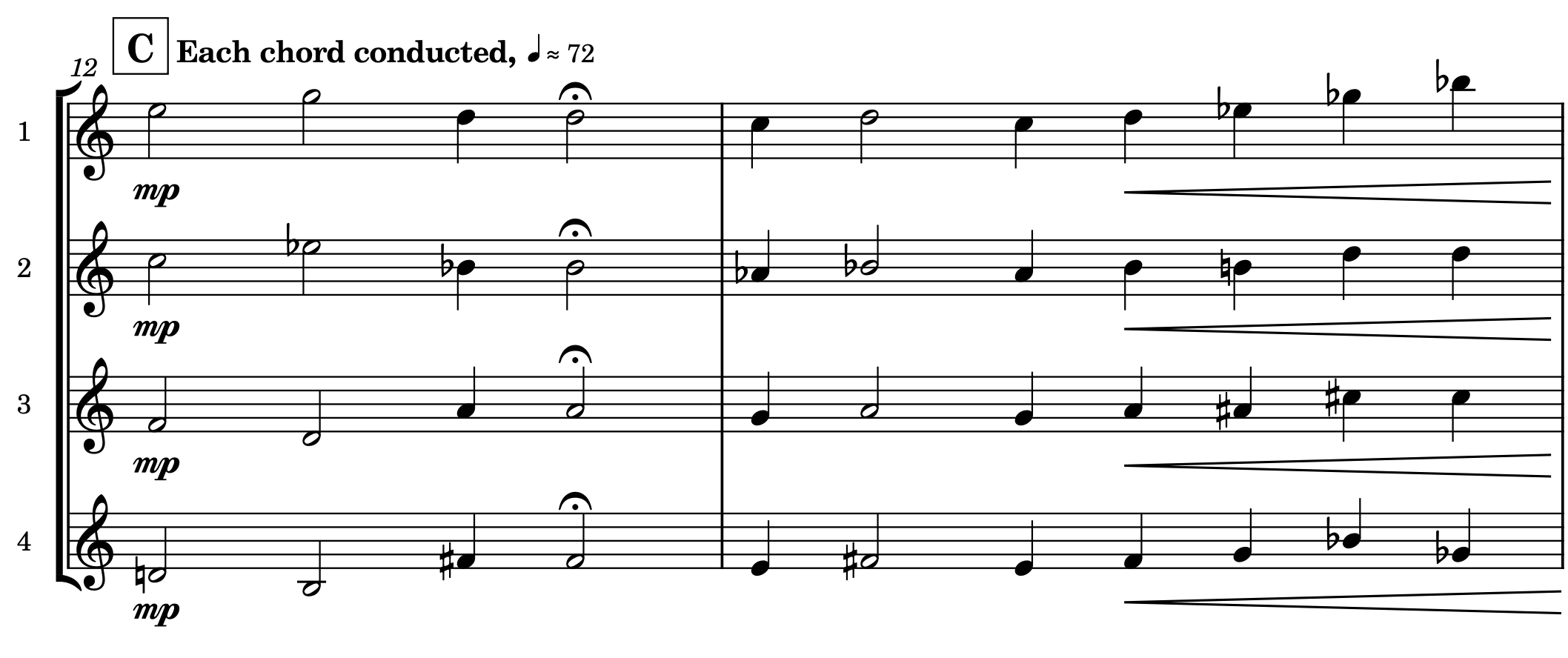

The next section, mm. 6-9, allows each player to decide the pace at which they move through a succession of pitches over a given period of time. For example in m. 6, players are given eight to ten seconds to move through six pitches. The result is somewhat similar to the opening section, however the difference is that individuals have the opportunity to diverge from one another a bit further. The beginning and ending of each one-measure phrase will be relatively stable, but the middle is a point of maximum divergence, as some players may choose to start quickly and end slowly, while others choose the opposite and others do something in between. This gives the individual players yet more control over the unfolding of the work, and greater responsibility for listening and reacting.

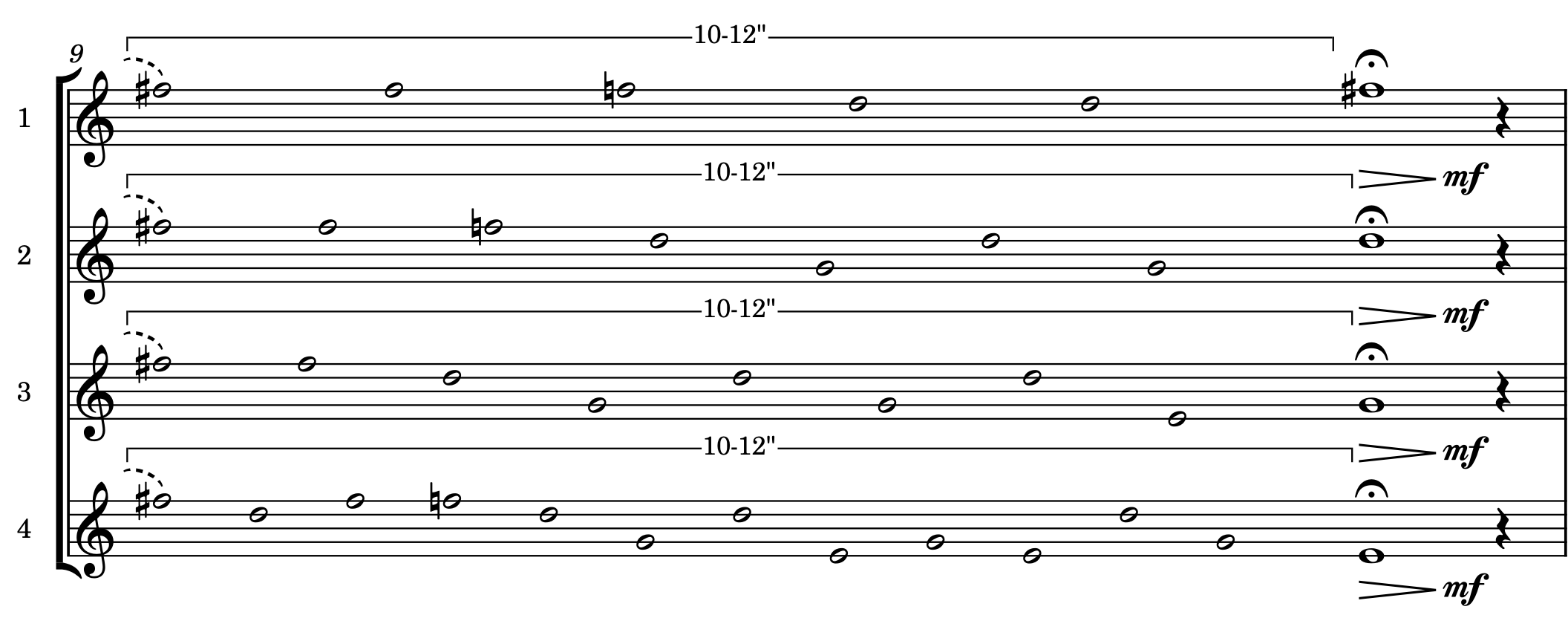

After a short transition (mm. 10-11) which refers to the latency-driven idea of the opening section (this time without the canon-like imitation), I present the most conventional chamber music texture of the work: a chorale. In this remote performance setting, each chord is conducted visually. Since there is sometimes some drift in audio-video synchronization of the videoconference, this can show some other implications of the network and software environments of the performance. The not-quite synchrony of this section concludes with the loudest section of the work, which is also the moment where players are least likely to hear one another and the least reliant on aural cues.

The next passage is a brief variation on the time-bracketed phrases of mm. 6-9. In it, players choose a moment within a time window to quickly swell from soft to loud and back to soft. My goal in this section is to highlight any quirks of the audio processing happening within the videoconference application. Fast dynamic changes can trip up compressors and cause them to behave strangely. Receiving a suddenly loud sound from one feed might cause the conference to drop audio from another feed entirely. The uncertainty here is coming from a combination of player choice and unpredictable audio processing algorithms. I like to think of the ensemble as playing Zoom like a musical instrument during these moments. And the piece concludes with a textural recapitulation of the follow-the-changing-leader idea which opens the piece.

The techniques I use are central to my conception of the piece. They are musical solutions to technical problems, which make Music for Social Distancing not simply tolerant of network delay, but in some ways reliant on it. This piece would not work the same way for an ensemble of musicians all sitting in the same room.

Performances

Music for Social Distancing was written in response to physical isolation that musicians at all levels were dealing with in their own ways. Because of the flexible nature of so many of the key elements of the work, the technical demands are relatively low, which has allowed the work be be performed by high school, university, and professional musicians. I want to briefly discuss some of the reception that it received from performers.

The first four groups4 to rehearse and perform Music for Social Distancing all did so within about a month of one another. I was pleasantly surprised at the number of groups that were interested in taking on such an unusual experiment. The first thing that all three ensemble directors told me was “We needed this” or “It felt so good to make music together again.” This to me is the biggest indicator that the work achieves at least some of the goals that I set out regarding an expression of chamber music collaborative spontaneity over a physical distance.

In addition to this positive feedback, I also heard about—and experienced in my own performance—a few notable challenges that could be addressed either technologically or through further exploration of compositional techniques.

All of the performances that I’m aware of so far have used Zoom as the videoconference platform, and all of them have struggled to varying degrees with Zoom’s audio processing. As much as I tried to account for this with the composition techniques I described earlier, there are still some serious limitations, particularly around the way Zoom selects individuals to be the “main” speaker. Certain timbres or frequencies seem to regularly push out others from the mix in a way that can’t be mitigated by any of the currently available audio settings in the application. Even with Zoom’s “Original Sound” feature enabled, there is still a certain amount of echo cancelation, dynamic compression, and data compression that is inescapable.5

Relatedly, some particularly loud instruments struggle to play within the dynamic range that is suitable for built-in microphones on most laptops. In terms of objective audio quality, having all players use specialized audio equipment could improve these concerns, but at the same time, I find the uneven sounds to have a pleasing verisimilitude that reflects how these technologies are used in their intended contexts. Having better ways to control audio clipping for louder instruments and better microphone options for mobile devices could dramatically improve the overall audio quality of the performance.

The last challenge with the work goes well beyond musical performance but is worth mentioning in this presentation because of the number of student musicians performing this work. It seems unavoidable to me that a performance of a work that requires certain computers, audio hardware, or Internet connectivity will shine a bright light on any discrepancies in technology access. Performing Music for Social Distancing is quite challenging in ensembles where some players are using devices with desktop operating systems, and others are using mobile devices or Chromebooks. It would be deeply unjust to tell a group of students that a particular rehearsal or performance opportunity is only available to students who have an instrument at home, a laptop that meets x requirements, and a broadband Internet connection of at least y megabits per second.

Performances of Music for Social Distancing all dealt with at least some of these issues, and yet all were successful on the whole. Some of these concerns may improve over time—such as software options or broadband availability—but others will require yet more creative solutions both in and out of my control as the composer.

Conclusions

I am presenting this around four months after social distancing became a shared social and cultural experience, and it feels at this moment as though it may be here for quite a while, as intimidating and depressing as that might be. Music for Social Distancing was an experiment in making music remotely as a group. The compositional techniques that I have described today could be explored much more deeply, and there are many more possibilities. I hope that I can contribute music that is thoughtfully constructed for these times. I don’t want to give up on chamber music simply because we can’t make it in the same ways we are used to. Rather than forcing traditional compositional techniques, textures, and styles to fit into the limitations of socially distant performance, I want to take what is available and makes music with it.

- As a shy midwesterner, I am very uncomfortable with writing a few thousand words about my own music, and I feel an appropriate amount of shame for posting it here on the blog. Ope. ↩

- Van Kerkhove, Maria. WHO Emergencies Conference on Coronavirus Disease Outbreak. World Health Organization, 20 March 2020. Accessed 1 August 2020. //www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/transcripts/who-audio-emergencies-coronavirus-press-conference-full-20mar2020.pdf ↩

- McCalla, James. Twentieth-Century Chamber Music, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Routledge, 2010. ↩

- Plano West Senior High School String Quartet, Ryan Ross, director; Susquehana University Symphony Orchestra, Jordan Smith, director; a Milliken University faculty mixed chamber ensemble, Corey Seapey, director; and Lone Star Youth Orchestra, Kevin Pearce, director. ↩

- As of this blog post in late August 2020, Zoom has announced in a blog post that they will be releasing a new “Advanced Audio” feature which eliminates even the echo cancelation and dynamic compression. The performance presented at the conference used Zoom for video with Cleanfeed for realtime(ish) audio to avoid compression. ↩